Are robots going to replace people’s jobs? (Part 1)

Since I started designing robots, especially humanoids, I’ve been asking myself the same set of questions again and again. Not as a philosophical exercise, but as a design tool.

What is this robot?

What does it actually do?

Where and in what context will it operate?

Who will work next to it?

Who will control it?

Who will buy it?

How will it really be used, day after day?

If you have worked in robotics, you already know the uncomfortable part. Most of these questions stay unanswered until very late in development, sometimes even until real deployment. There are reasons for that, but the result is that we often design robots long before we fully understand the job they are supposed to fit into.

This brings me to a question that keeps coming back in media and public discussions:

Are robots going to replace people’s jobs?

I do not think this has a simple yes or no answer. What I can do is explain how jobs and tasks are viewed from a robotics perspective, what robots are actually good at, and where the real limits are. From there, the picture becomes much clearer.

Jobs are not tasks

Most robots today are designed to perform one task, or a small set of tasks. Humanoids and so-called general purpose robots are the exception, not the norm.

The first distinction that matters is the difference between a job and a task.

A job is almost never a single activity. It is a bundle of:

Planned and structured tasks

Unplanned and unstructured tasks

Regulations, risks, responsibilities, and quality expectations

The mix between structured and unstructured tasks often defines how much experience and judgment is required.

Take a firefighter. The job is fundamentally unplanned. You never know when the mission starts, and no two scenes are the same. The environment is chaotic, conditions change fast, and emotional and social judgment matters.

Now take a worker on an assembly line installing a car headlight. The task is predefined, standardized, and highly structured. The environment is controlled. The next move is known in advance. Creativity is not only unnecessary here, it can be dangerous.

These two jobs sit at opposite ends of a spectrum.

Most real jobs live somewhere in between. They combine structured and unstructured tasks in different ratios.

And there is another layer that often gets ignored:

Replacing a job requires replacing accountability, not just execution.

Someone is responsible when things go wrong. Someone signs off on quality, safety, and compliance. Today, that responsibility almost always belongs to a human, even when machines are involved.

This alone makes full job replacement far harder than task automation.

What robots are actually good at

So the real question becomes:

Can a robot perform the whole job, or only specific tasks within it?

Before answering that, it helps to briefly touch on Moravec’s paradox. In simple terms, it states that what humans find hard, like math or logic, is often easy for computers, while what humans find effortless, like walking or manipulating objects, is extremely hard for machines.

My interpretation is practical rather than theoretical. Tasks that humans evolved over millions of years, especially sensorimotor and embodied skills, are deeply compressed into intuition. We perform them without explicit reasoning.

Translating that into hardware, perception, control, and failure handling is expensive, fragile, and slow to scale.

Tasks humans invented relatively recently, like formal logic, symbolic math, or structured language, are easier to encode, test, and replicate. This is not really about intelligence. It is about embodiment, physics, and interaction with the real world.

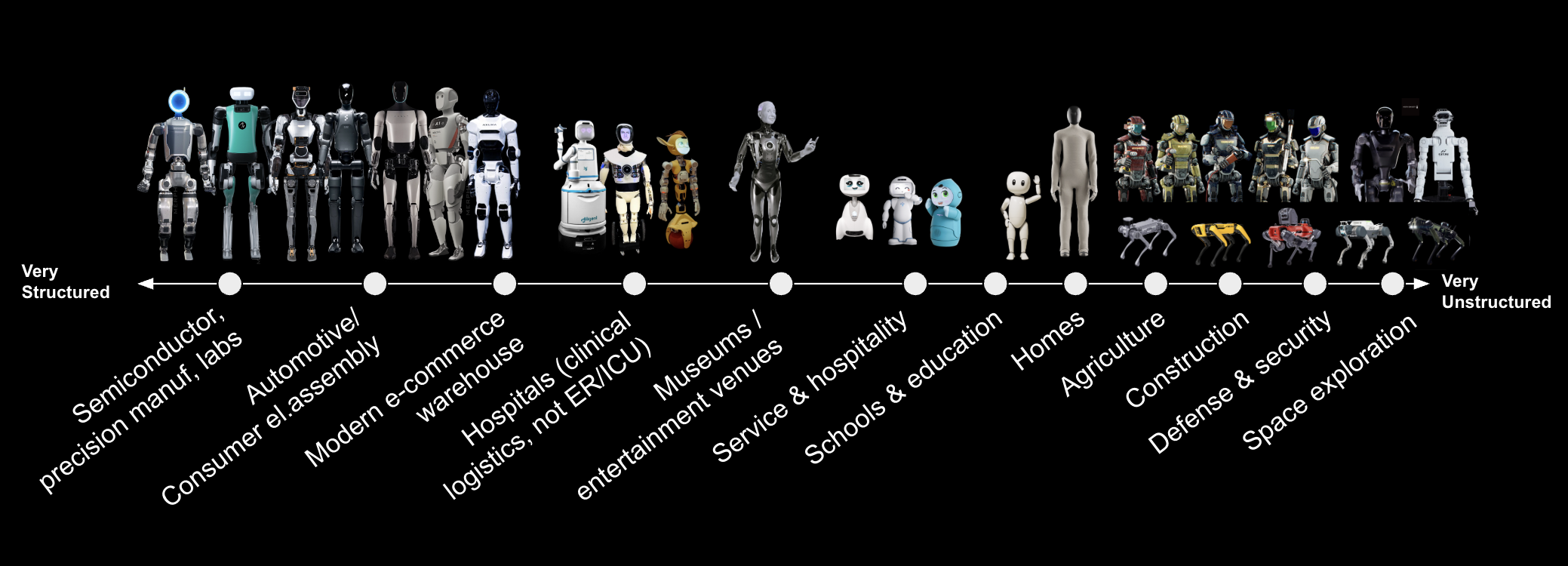

Environment matters as much as intelligence

A typical robot sits at the intersection of three things:

Motion control and manipulation

Perception of Environmental context

Human collaboration

The environment defines how hard the problem really is.

Is it structured or unstructured?

Are objects standardized or variable?

Is there supporting infrastructure?

What happens when something fails?

As a rule of thumb, when a task is well defined, has clear steps, and enough economic value, it can be automated with a specialized robot.

Once a task spans multiple environments, contains undefined steps, or requires constant adaptation, complexity grows much faster than value.

An intuitive example: opening a door

Imagine a robot that needs to open every door it encounters as part of another job.

To do that, it needs to:

Recognize that something is a door

Find the handle

Decide how to grip it

Apply the right force

Understand which way the door opens

Open it enough

Move through a narrow passage

Avoid hitting the frame

Close the door properly

You do this without thinking. For a robot, every one of these steps is a potential failure mode.

Now think about what kind of robot this requires. A human-like end effector, because doors are designed for humans. Multiple joints to hold the door while moving through it. A body that fits through tight spaces without getting stuck.

Then comes the uncomfortable question:

What is the value of opening a door?

Opening a door is not a job. It is a small part of many jobs. The cost of building a robot that can reliably open any door is rarely justified by the value of that task alone.

Compare that to a workstation robot

Now take a very different example.

A robot sitting at a workstation, soldering low-volume custom PCBs.

The task is constrained. The environment is controlled. The objects are known. The value is clear.

This robot likely needs:

Two simple arms

Vision tuned for a small workspace

Specialized end effectors

No legs, no mobility, no generality

This is why industrial robotics works. We minimize morphology, intelligence, and uncertainty to the absolute minimum required for the task.

A useful comparison: AI did not replace jobs either

It is worth briefly looking at AI, because we have already lived through a similar wave of hype.

AI has made enormous progress in language, vision, and reasoning. It clearly outperforms humans in many narrow domains. And yet, despite all the buzz, it has not truly replaced full jobs.

Instead, it has:

Automated parts of jobs

Accelerated certain tasks

Shifted how humans work

Editors still exist. Programmers still exist. Designers still exist. What changed is how tasks are distributed between humans and tools, and who holds responsibility.

Robotics follows the same pattern, with one important difference: failures in robotics are physical, visible, and often costly. That slows adoption even further.

Why robots replace tasks, not jobs

Today, we already have millions of robots performing highly specialized tasks. None of them has fully replaced a job. They remove parts of jobs.

What we are doing now in robotics is gradually expanding that envelope. Making robots slightly more flexible, slightly more adaptive, able to handle more variation.

But every added capability introduces new challenges:

Hardware reliability

Perception failures

Safety and certification

Cost versus value

This is not just a technical problem. It is an economic, organizational, and accountability problem.

So when we say robots will replace jobs, we should slow down and ask:

Which job?

Which tasks within that job?

Under what conditions?

With what reliability?

And at what cost, compared to a human?

Where this leaves us

Robots taking over entire jobs is not something that happens suddenly. It is a gradual process driven by task-level automation, human collaboration, and economics.

What robots can do today, and in the foreseeable future, is take over certain tasks. Often boring, repetitive, or physically demanding ones. Almost always with humans still in the loop and accountable.

Human-robot collaboration is the missing piece here, and that is what I will talk about in the next part.